-Papa! what's money?

-What is money, Paul? Money?

-Yes, what is money?

-Gold, and silver, and copper. Guineas, shillings, half-pence. You know what they are?

-Oh yes, I know what they are. I don't mean that, Papa. I mean what's money after all?

Little Paul Dombey, Dombey and Son, by Charles Dickens (1848)

FYROM's Slavomacedonism, Part II: recent developments and geopolitical context

Note: This article originally appeared on Oct. 29, 2008 on ZNet. No changes have been made, apart from formatting and reassigning certain dead links.

The period after 1991

After the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991, Greek public opinion came face to face with a bitter reality. The "Socialist Republic of Macedonia", one of the Federated States of the former Yugoslav Federative Republic, sought international recognition under the name "Republic of Macedonia". Since its creation in 1945, when it was renamed from Vardarska Banovina to "People's Republic of Macedonia" (and then to SRM), and as long it was part of Yugoslavia, it was possible for Greek authorities to turn a blind eye on its very existence. Greek governments, under NATO directives, collectively chose not to question Tito's contentions on Macedonia. His defiant stance toward Stalin and the USSR made him a NATO favorite in the region. In addition, as Kofos states [1]:

On the political level, successive Greek governments in the decades following the Civil War shared the view that Yugoslavia was a useful buffer state on the fringes of the Soviet-dominated communist world. Despite frequent irritants from the local government, press, and radio in Skopje, Athens had never raised any objections to the constitutional framework of the FSR of Yugoslavia, nor had it ever questioned its internal administrative structure of federate republics. Indeed, a Greek consulate general continued to function in Skopje, maintaining normal de facto relations with the authorities of the Republic, although officially it was accredited to the federal government in Belgrade. On the other hand, however, official Greek policy, supported by all major Greek political parties, rejected the existence of a "Macedonian" nation. This denial, however, did not negate the existence of a separate Slavic people in the SRM, but objected to its Macedonian name which was considered a constituent element of Greek cultural heritage.[2]

and then:

[P]rior to the mid-1980s, with the exception of occasional flare ups in the press, there was little serious debate in Greece about the various aspects of the Macedonian issue. Any discussion that did occur was limited to a confined number of academics, journalists, and politicians, centered mainly in Thessaloniki.

The Greek handling

However, all that arrangement collapsed and Greece found itself next to a neighbor whose inhabitants had been raised as "Macedonians" (Makedonci) for more than four decades. The initial reflexive and unanimous reaction of Greek political parties was to vehemently oppose the request of the newly independent state: no state outside Greece could bear the name of Macedonia or its derivatives. However, this position was in sharp contrast with the neglect of previous decades. Not much later, different approaches were adopted within the conservative government of the New Democracy party; Foreign Affairs minister Antonis Samaras opted for a no compromise, while PM Constantinos Mitsotakis sought a compromising solution. The maximalist, "no Macedonia or its derivatives" view was exploited by the major opposition party of PASOK, under Andreas Papandreou, as a tactic to force the government into a tougher bargaining position. On December 17, 1991, the EC/EU foreign ministers issued a declaration asking "for constitutional and political guarantees ensuring that [the applicant state] has no territorial claims towards a neighboring Community State [Greece] and that it will conduct no hostile propaganda activities versus a neighboring Community State, including the use of a denomination which implies territorial claims." On April 13, 1992, the Council of Party Leaders convened under President of the Republic Constantinos Karamanlis (uncle of the present PM) and adopted the maximalist line (with the sole exception of only KKE's Aleka Paparriga). At that point Samaras was dismissed by Mitsotakis, who took over the Foreign Affairs portfolio himself. However, Mitsotakis adopted himself the maximalist position outmaneuvering his party's internal opposition and Papandreou's as well.

European solidarity was affirmed on May 2 (Gimaraes) and June 26-27 (Lisbon) by the EU leaders who declared their readiness to acknowledge the new state, so long as a settlement with Greece had been reached. This was a diplomatic quasi-victory for Greece, who seemed to achieve all its goals. However, the war in Northern Yugoslavia, raging in 1992, gave President Kiro Gligorov more convincing arguments to support his own maximalist position: immediate recognition would foster stability in the region. Thus, when a year later, he petitioned for UN membership, thereby circumventing the EU declarations, this was granted (Decision 817/ 7.4.1993). However, membership was under the provisional name "Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" (FYROM), and on condition that FYROM would remove the "Vergina Sun" (emblem of the ancient Macedonian dynasty) from its flag.

In May 1993, UN mediators Lord Owen and Cyrus Vance presented a draft treaty settling various issues. However, Mitsotakis was now found trapped in the maximalist line he had previously adopted. The draft was rejected and in September his slim majority was lost after two of his deputies deserted him.

PASOK won the next elections with Papandreou becoming PM in October 1993. He adopted the same maximalist, refusing any name containing "Macedonia" or its derivatives. As a number of countries started recognizing the new country as FYROM, endorsing the UN decision, Papandreou further hardened his position by deciding on an embargo against FYROM in February 1994. This manoeuver consolidated national sentiment around him and pulled the rug under the feet of New Democracy's new leader (Miltiadis Evert) who had also taken a hard line. After Cyrus Vance's initiative, talks resumed on March 1994 and an Interim Accord was signed in September 1995. Greece would thereby agree to recognize the new state as FYROM and lift the embargo, while FYROM would remove the Vergina sun from its flag and agree to revise articles 3 and 49 of its Constitution that Greece considered as irredentist. In addition according to the Accord, "the Party of the First Part [Greece] agrees not to object to the application by or the membership of the Party of the Second Part [FYROM] in international, multilateral and regional organizations and institutions of which the Party of the First Part is a member; however, the Party of the First Part reserves the right to object to any membership referred to above if and to the extent the Party of the Second Part is to be referred to in such organization or institution differently than in paragraph 2 of United Nations Security Council resolution 817 (1993)." (Article 11, Par. 1).

This was a turning point in many terms. As Kofos writes: "Few, if any, had noticed, even prior to the conclusion of the agreement, a nuance in the Greek government's public statements, which proclaimed that "the Greek government will never recognize a state bearing the name Macedonia or its derivatives" a phrasing that had substituted the traditional line that "the new state should not bear the name Macedonia or derivatives of that name." Typical of Papandreou, while saying one thing to the masses, he let them understand the opposite.

In January 1996, due to his faltering health, Papandreou was replaced at the helm of PASOK and as PM by Kostas Simitis, one of the "modernists" of the party, far from its "patriotic" wing. Being more prone to create business opportunities for Greek enterprises, he preferred a quick normalization by accommodating a compromise. Gligorov seized the opportunity to consolidate his own intransigence: in summer of 1997, the government at Skopje submitted to Cyrus Vance its official position on the name issue. That was its constitutional name, i.e. simply "Republic of Macedonia".

FYROM handling

Even before Yugoslavia's dissolution, in October 1989, public demonstrations were organized in Skopje, demanding "reunification of Macedonia", and declaring that "Solun [Salonica] is ours". The VMRO-DMMNE (Inner Macedonian Revolutionary Organization-Democratic Party of Macedonian National Unity), a political party founded in 1990, as the resurrection of the original VMRO organization, adopted a nationalist line. Although not of a Bulgarian orientation like its predecessor, it too chose to proclaim a unification of the three Macedonian regions (of Pirin in Bulgaria, of the Aegean in Greece and of the Vardar, i.e. the former SRM). It also chose the Vergina's sun and the Bulgarian lion as its symbols.

The Parliament that formed after the first Parliamentary election in November-December 1990 adopted the constitutional amendment for removing the "Socialist" adjective from the official name of the country (April 16, 1991), and on June 7 the same year, the new name "Republic of Macedonia" was officially established. A referendum of September 8, 1991 endorsed the new Republic's independence from Yugoslavia, with Kiro Gligorov as its first President.

During 1992 and 1993, Gligorov's government issued new school textbooks that showed "geographical ethnic boundaries" encompassing the whole of Greek Macedonia; the country's flag carried the Vergina Sun, King Phillip's symbol. However, this line was in disconcert with the line expressed in international fora. In a report by Dusko Dodev, Mr. Gligorov held on to the description of "Macedonian", renouncing however, any connection to the ancient Macedonians: "We carried this name for centuries. We are Macedonians but we are Slav Macedonians. That's who we are! We have no connection to Alexander the Greek and his Macedonia. The ancient Macedonians no longer exist, they had disappeared from history long time ago. Our ancestors came here in the 5th and 6th century (A.D)." (Toronto Star, March 15, 1992). The same view was expressed during an official visit to Albania's PM Sali Berisha in 1992, when he said: "We are Slavs, we have no connection with Alexander the Great, we came to this area in the 6th century A.D."). This duality persisted throughout the 1990's. On 22 January 1999, Ambassador of the FYROM to USA, Ljubica Achevska gave a speech on the present situation in the Balkans. In answering questions at the end of her speech Mrs. Acevshka said: "We do not claim to be descendants of Alexander the Great ...; Greece is Macedonia';s second largest trading partner, and its number one investor. Instead of opting for war, we have chosen the mediation of the United Nations, with talks on the ambassadorial level under Mr. Vance and Mr. Nemitz." In reply to another question about the ethnic origin of the people of FYROM, Ambassador Achevska stated that "we are Slavs and we speak a Slav language". On 24 February 1999, in an interview with the Ottawa Citizen, Gyordan Veselinov, FYROM'S Ambassador to Canada, admitted, "We are not related to the northern Greeks who produced leaders like Philip and Alexander the Great. We are a Slav people and our language is closely related to Bulgarian [...] There is some confusion about the identity of the people of my country". Moreover, the FM of FYROM, Slobodan Casule, in an interview to Utrinski Vesnik of Skopje on December 29, 2001, said that he mentioned to the Foreign Minister of Bulgaria, Solomon Pasi, that they "belong to the same Slav people".

This duality continued until recently, when the airport of Skopje was renamed to "Alexander the Great Airport" at the beginning of 2007.

The internal politics of FYROM were heavily influenced by the insurgency of the Albanian minority during 2001. Traditionally, there was an important Albanian minority within the SRM/FYROM. Today, 25% of FYROM's population are ethnic Albanians (2002 census). Furthermore, these do not ascribe to any "Macedonian" descent. As we mentioned in Part I, the Albanian minority had repeatedly protested its treatment by the state; a state founded for its "Makedonci" population and not for its minorities. In January 2001 the National Liberation Army (NLA), an Albanian paramilitary, started attacks against government forces, in a way similar to that of the KLA in Kosovo. The armed conflicts reached the brink of civil war, before the US and the EU intervened, by having the two sides sign the Ohrid Framework Agreement in August 13, 2001. This would ensure larger constitutional and legislative rights for the minorities, particularly so for the Albanian minority.

For the implementation of this agreement, under US and European pressures, the SDSM-DUI governing coalition brought to the parliament legislation redrawing local boundaries and giving ethnic Albanians greater local autonomy in areas where they predominate. The legislation, which was approved in August 2004, involved territorial redistributions, which would create larger, more concentrated Albanian-majority areas. As such, it was unacceptable by the Slavophones and other non-Albanian ethnic groups of the country. Thus, a referendum was initiated by the opposition, which among others, was backed by the VMRO-DPMNE (which was in the opposition at the time). This referendum took place on November 7, 2004 with the question: "Do you wish to endorse your government's proposal for territorial redistricting, or do you wish for them to go back to the drawing board and come up with a new (and hopefully better) plan?" The SDSM-DUI government coalition called for a boycott to the referendum, since it would require a turnout of 50%, or more, for it to be legally binding. With a combination of intimidation and bribery, and to great EU/US relief, the voter turnout was only 26.2%, which meant that the referendum was defeated. Of those 26.2%, 95.4% votes were against the new redistribution and only 4.6% voted for it. Due to the difficult position of the government brought on by these measures, US President Bush announced recognition of the country as the "Republic of Macedonia" to counter popular discontent.

The recent US involvement

The US developed a strong interest in post-Cold War Europe, particularly in the Balkans and Eastern Europe. As part of that interest, they took it upon them to arbitrate the naming dispute, starting with Bill Clinton. In 1994 Clinton appointed Matthew Nimetz as his special envoy for the negotiations (from March 1994 through September 1995). Among a host of other appointments, Nimetz had been Lyndon Johnson's staff Assistant and later Counselor of the US State Department appointed by Jimmy Carter. After Cyrus Vance's resignation he was appointed (December 12, 1999) as a personal envoy by Kofi Anan for the naming issue. Today he is also a board member of the Non-Government Organization Center for Democracy and Reconciliation in Southeast Europe (CDRSEE). CDRSEE has been funded, among others, by the USAID, the NED and two Soros foundations, the Fund for an open society - Serbia and the Foundation Open Society Institute Macedonia. It is noteworthy that it was no other than the special envoy of the US president that then became personal envoy of the UN Secretary-General.

The Greece-FYROM conflict remained in an effective limbo after 1999, in which time as many as 100 States came to recognize FYROM as "Republic of Macedonia" on a bilateral level. It was violently revived in 2004, as we mentioned in Part I, when US President G. W. Bush recognized FYROM with its Constitutional name in an explicit effort to stabilize its inherently unstable government.

Bush justified his decision to the Greek PM Karamanlis in a letter, dated November 16, 2004: "I realize our decision to recognize Macedonia by its constitutional name generated significant controversy in Greece. [...] Our single goal was to bolster stability in Macedonia and its neighborhood at a crucial moment [...] We will embrace any solution that emerges from these (U.N.-led) negotiations [...] The United States has to act quickly and decisively, given the speed of events and the high stakes surrounding Macedonia's November 7 referendum."

The NATO summit in Bucharest and the Greek veto

As we mentioned, a pivotal part of US geopolitical strategy is the expansion of NATO to the East, encircling Russia, contrary to the Reagan-Gorbachev understanding. This expansion includes former Warsaw Pact countries (Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Romania) as well as former USSR Republics (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania). Earlier this year (April 2008), Croatia, Albania, FYROM and Georgia were considered by the US to be invited during the NATO summit.

Greece's position as a NATO and EU member, gave it the privilege to veto FYROM's accession into these international organizations, had the name issue not been resolved. Prior to the summit, pressure was mounted from the US for Greece not to veto FYROM's accession. At thattime the Greek government consolidated its position for a unique, composite name, with a geographical descriptor used for all purposes (erga omnes). Despite all US pressure, the unthinkable happened: Greece did veto FYROM's accession, against Bush and Rice pressures. Following that decision, high ranking officials and journalists undertook to discredit the Greek position:

-Assistant Secretary of State Daniel Fried declared: "...Macedonian language exists. Macedonian people exist. We teach Macedonian at the Foreign Service Institute. There is also the historic Macedonian province, which is different from the country. And it's important. It's quite clear that the government in Skopje, what we Americans call the Government of Macedonia, has no claims [against Greece]. We recognize the difference between the historic territory of Macedonia, which is, of course, much larger than the current country."

-The New York Times editorial board published an article on their blog, titled: "Shame on Greece: Messing with Macedonia", in which among other, they stated that "Now they [President Bush and the EU leaders] must ratchet up the pressure on Greece to achieve that compromise so that NATO's insult to Macedonia is reversed as quickly as possible."

Meanwhile the insistence of the Bush administration to include FYROM into NATO was reflected by the Bucharest summit declaration: "20. ... Therefore we agreed that an invitation to the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia will be extended as soon as a mutually acceptable solution to the name issue has been reached. We encourage the negotiations to be resumed without delay and expect them to be concluded as soon as possible." Shortly thereafter (May 7, 2008), USA and FYROM signed a "Declaration of Strategic Partnership and Cooperation Between the United States of America and the Republic of Macedonia". Though this short declaration is vague and hardly binding to the next US administration, it can be viewed as an effort to soften the blow.

Letter diplomacy and a sudden change of the agenda: minorities are now the issue

Minorities and human rights issues have been traditionally used by major powers as a pretext for intervention, undermining of sovereignty and, eventually, military action against other countries. Such pretexts were used prior to Hitler's invasion in Czechoslovakia (to protect ethnic Germans in Sudetenland), or by NATO to bomb Yugoslavia (to protect ethnic Albanians in Kosovo). As Xavier Solana, Secretary General of NATO put it during a press conference, human rights can supersede sovereignty. Even if interventions do not always escalate to military action, human rights issues still provide a powerful means of coercion of foreign governments. It is therefore not illogical to search for such tactics during the current conflict. Felice Gaer, US Commissioner on International Religious Freedom to the OSCE reported on September 28, 2005: "Greece's poor treatment of its ethnic Turkish, Albanian and Macedonian minorities is still a concern of the United States. Greece continues to displace some Romani communities in a manner inconsistent with Greek law." Mrs Gaer's explicit recognition of a "Macedonian minority" in Greece is a prelude to recent developments.

Last summer, FYROM's president Mr Nikola Gruevski, disseminated a series of letters to the Greek PM Constantinos Karamanlis (July 14), to the European Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso (July 21) and the UN General Secretary Ban-Ki Moon (July 22) and finally with a series of letters to NATO, the OSCE and the G8 states. In his letter to Mr Karamanlis, Mr Gruevski's requests from Greece the reclamation of properties of "ethnic Macedonians" having abandoned Greece during the Greek civil war during the late 1940's, "...recognizing the Macedonian minority in the Republic of Greece", "regulating the use of the Macedonian language in local institutions ...", etc. [3]

In trying to decipher Mr. Gruevski's sudden change of tune, we will be assisted by expert opinions of US foreign policy makers. Although Mr. Gruevski was caricaturized by Greek media for his seemingly erratic strategy, and his letters were characterized as "ridiculous" by the Greek Foreign Ministry, we may conclude that it was not entirely his strategy and perhaps not so erratic after all.

Following the Greek veto at Bucharest, Edward P. Joseph published an article in the Spiegel (June 2nd, 2008), titled "How to Solve the Greek Dispute over Macedonia's Name" (part 1 and part 2). In part 2 he states that:

[...] NATO, where American influence is greatest, offers the best vehicle for success.

The solution, ironically, lies in embracing -- to the fullest extent -- the Greek assertion that the name dispute is now a multilateral matter ... the United States should move to convene the North Atlantic Council (NAC) for an urgent session to accept the Greek interpretation of the Bucharest communiqué. But it should not stop there. The NAC must simultaneously ask the NATO Secretary General to provide a full and complete report on all dimensions of the name dispute within 30 days. The NAC resolution should cite the requirement in NATO's founding document for peaceful and friendly international relations and related obligations in the charter of the United Nations (particularly on human rights). As a result, the NATO Secretary General will have to turn to an array of organizations and individuals, including the UN mediator, the OSCE High Commissioner on National Minorities, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and private organizations like Human Rights Watch.

In short, NATO would begin to move down the very road toward the examination of Macedonian minority rights in Greece that sits at the root of the Greek objection to Macedonia's name in the first place. The Greek government would pay a heavy political price for such an outcome.

Only by introducing the full dimension of the problem, including the question of the Macedonian minority in Greece, will Athens have an incentive to compromise -- and will more instability be averted.

In order to evaluate the weight of these opinions, we should note that Joseph His articles have been published in Foreign Affairs, The New York Times, The Washington Post and in Z-word. He is also Visiting Scholar and Professorial Lecturer at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, DC. We should therefore ascribe the appropriate significance to his views, which should not be considered as simply personal opinions.

On October 19, 2008, the Sunday weekly "Ethnos tis Kyriakis" revealed a confidential telegram from the US Ambassador in Skopje, Gillian Milovanovic, dated July 29, 2008. The telegram addressed to the National Security Council, the Secretaries of State and Defense proposed a "formula" of arrangements acceptable to the FYROM government. Among other things the telegram stated: "Embassy Skopje assesses that in the context of an agreement that clears the way for NATO membership and the start of EU accession talks, the Macedonian government would ultimately accept the following terms: Name: Republic of Northern Macedonia (or: Republic of North Macedonia). Scope: In all international organizations, plus bilaterally, by any country that does not want to use the constitutional name (although we have not discussed this explicitly, presumably international agreements would follow the same pattern with multilateral ones having the option). Macedonia would use its constitutional name in referring to itself, on passports, product labels, in the media etc. Identity: The Language and nationality would be called Macedonian, but this could be handled tacitly, perhaps as a subsequent annex to a UNSCR, or some other internal UN document not subject to Greek review/approval. Bottom line is Macedonia needs assurance that their language nationality, etc. would continue to be called Macedonian, not North Macedonian."

On October 8, 2008, about 3 months after Joseph's article and 2 months after Milovanovic's telegram, M. Nimetz published his revised proposals. Therein, he proposed (i) the name "Republic of North(ern) Macedonia" for use in international organizations, treaties and meetings, (ii) a "recommendation" from the UN Security Council's to UN member-states to make use of this name on a bilateral level, (iii) the retention of the constitutional name "Republic of Macedonia", and (iv) the use of the adjectives "Macedonia/Macedonian" for internal purposes (e.g. passports, citizenship) and trade labels. Nothing is explicitly mentioned of language and nationality, neither for, or against the use of the "Macedonian" adjective. The similarities of these proposals regarding "Name" and "Scope" and the absence of reference to "Identity" fall very close to Ambassador Milovanovic's suggestions as transmitted to her telegram.

On September 2008, three months after Mr Joseph's article, the UN dispatched Independent Expert on Minority Issues, Gay J. McDougall, to study the "minority issues" in Greece. McDougall, who was previously a lawyer for the Debevoise, Plimpton, Lyons & Gates law firm, was appointed (among other positions) Executive Director of Global Rights (September 1994) and UN Independent Expert for the overseeing of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (1998). McDougall, effectively a "Human Rights specialist", crisscrossed Northern Greece in September 2008, in search of the oppressed "Macedonian minority". Although her upbringing in segregated Atlanta predisposes one to believe the sincerity of her intentions, the context in which she was found to operate makes one doubt the depth of her knowledge on the subject. McDougall, visited several cities systematically avoiding to meet local authorities. In Edessa (September 16th), she met with members of the Rainbow Party, a Greek political party proclaiming to represent the "Macedonian minority" in Greece. Greek local media, which were alerted of her visit, tried to cover this meeting, in which no more than 20 people participated. However, it seemed that McDougall wanted to keep this meeting secret. Upon seeing local TV station and newspaper cameras, she fled the room commenting "I'm not here!", obviously irritated. She refused to answer newspaper reporter's Anastasios Boulgouris' questions ("Logos tis Pellas" newspaper), while asking him not to take her picture.

It would be therefore plausible to assume that the US tactics on the Greece-FYROM issue can be summarized as follows: Solve the issue of NATO accession by shifting the discussion from the name conflict to minorities. Have FYROM take half a step back on the name issue, and two steps forward on minorities issues. The very existence of such minorities will be decided upon by a committee that Greece cannot review nor veto, through an internal document. The question of "Macedonian citizenship" for the citizens of FYROM will also be dealt with internally and tacitly. Facing an undesirable recognition of a Macedonian minority in Greece the Greek government will be more susceptible to accept such a fait accompli. The name issue will thus be resolved in a roundabout way. Mr Gruevski's torrent of letters, raising minorities issues, followed Mr Joseph's article only a month-and-a-half later.

The "ethnic Macedonian minority"

"Slavomacedonian minority" in Greece

But what about the "Macedonian minority" in Greece? As noted in Part I, there is a Slavophone population in Greece, along with other linguistic communities, like Vlachs, Pomaks, Roma (Gypsies), Arvanites (Christian Orthodox Albanophones) and Turkophone Muslims. Many Greek towns, villages, mountains and rivers bear toponyms in several of these languages. However, this linguistic identity diverges from national self-identification (again, see Part I). As an example we may mention Metsovo, a Greek village, whose name means "Bear village" in Slav. Metsovo used to be a major commercial center in the 19th century, with its major population being Vlachs. It has given birth to many prominent Greeks, of which we mention the great benefactor Georgios Averof. His name is distinctly Slavic, he was of Vlach origin, but he was a great Greek patriot and benefactor who donated large sums of money to the Greek State. A sum of that money was destined for the purchase of a warship which would bear his name. The Battleship Averof was one of the main Greek weapons during the Balkan wars. Also, we may mention Souli, a Greek region whose name is probably Albanian and means "Mountaintop". Its inhabitants were bilingual (Greek and Albanian-speaking), Christian Orthodox and fought against the Ottomans during the Greek revolution. They were considered as Greeks even by the Ottomans, and they fought alongside the rest of the Greeks during the revolution. Similarly, many fighters against the Ottoman rule during the Greek revolution (1821) were Slavophones of Greek conscience.

Thus, we should examine the linguistic communities in Greece within that context to draw safe conclusions concerning the correlation between language and national identification (an African-American speaking ebonics may just as well serve in the US Army and be very patriotic about it). These are found often to diverge, partly due to the Hellenizing effect of the Orthodox church to its Christian subjects of the region until the 19th century (see comment by Kofos in Part I). Focusing our discussion to the Slavophone Greeks we should remind that the Slavophone population of Macedonia numbered 80 thousand people after 1926. However, they do not ascribe to a Slavomacedonian national identity.

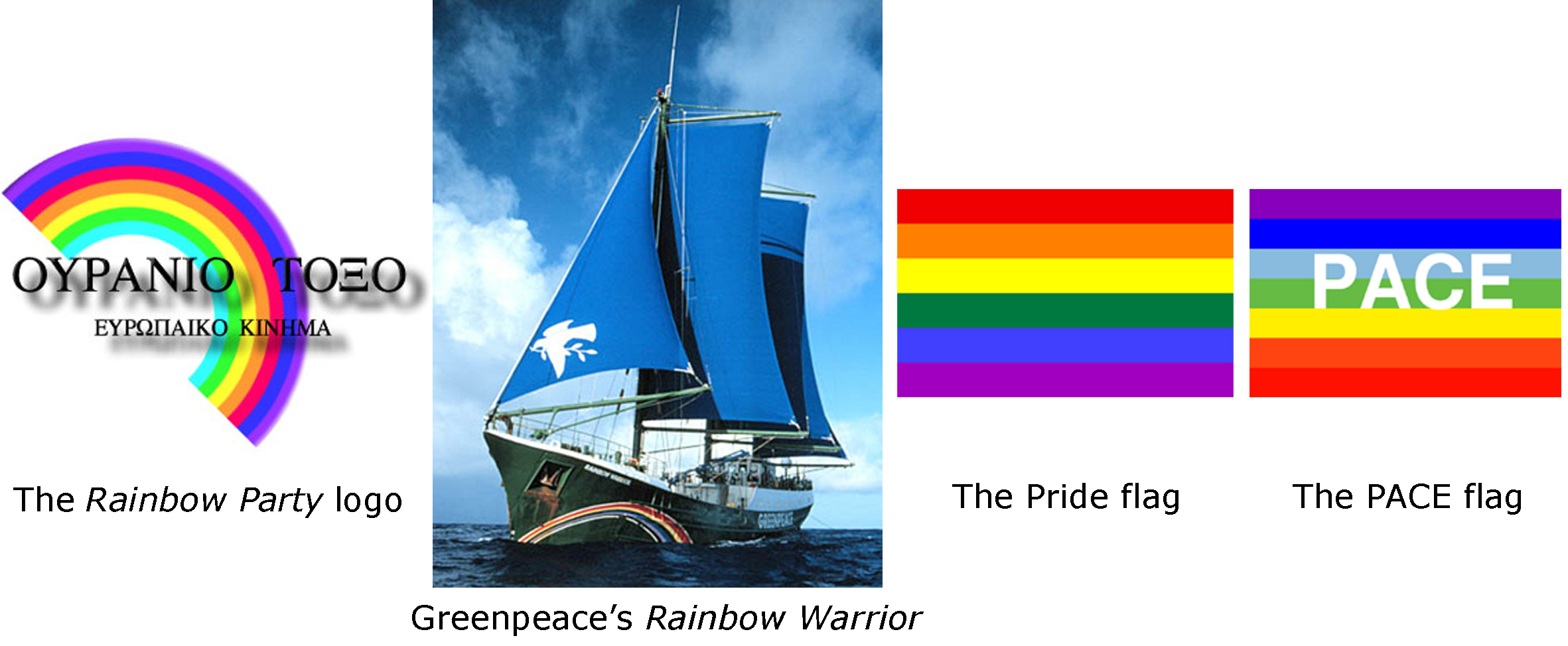

The political party proclaiming to represent this minority in Greece is "Rainbow", a member of the "European Free Alliance", "a European Political Party which unites progressive, nationalist, regionalist and autonomist parties in the European Union". Surprisingly though, the party's logo and name neither state explicitly, nor reflect its views and agenda. Instead they are designed in such a way that Rainbow could be mistaken for a pacifist party (similarity with the PACE banner), an environmentalist party (similarity with the "Rainbow warrior" markings), or even a homosexual rights party (similarity with the pride banner). It could also be confused with the Italian Leftist Rainbow coalition, or Rev. Jesse Jackson's Rainbow Coalition:

Nevertheless, the Rainbow party exhibits a very low electoral representation. Rainbow obtained 4.951 votes (0.08%) in the 1999 European Parliament Elections and 6.176 votes (0.10%) in the 2004 European Parliament Elections, while it has never participated in national elections. These low rates should also be taken into account by considering that smaller parties are favored during European Parliament Elections.[4] These electoral results of Rainbow suggest that it fails to represent the Slavophone community in Greece, neither in political nor in ethnic terms.

"Slavomacedonian" refugees from Greece

Moreover, we should also examine Mr Gruevski's allegations about expatriated "Aegean Macedonian" refugees from Greece and their rights to reclaim properties. It is true that many Slavophone fighters from Macedonia first sided with Bulgaria and then (after the collapse of the axis) instantaneously joined the communist ranks of the Greek EAM and the Yugoslav SNOF and NOF. From these bastions they were found, on many occasions, fighting against the Greek state and Greek territorial integrity; from the Bulgarian side by siding with the fascist VMRO and Ohrana organizations; from the communist side by siding with the Greek EAM and the pro-Yugoslav SNOF/NOF. In both cases, however, they fought for the secession of Greek Macedonian territories (won during the Balkan wars of 1912-13) and their eventual annexation to Bulgaria or Yugoslavia. It is not surprising, given the situation at the time, that they were persecuted by the Greek state along with many Greek (non Slavophone) Nazi collaborators or communists. Flight to Albania and Yugoslavia (and then to other Socialist countries) was their only alternative. Along with them, several thousand children (mostly of Communist fighters) were also moved to Socialist countries by the Democratic Army. The exact number is not known, however it is estimated to be somewhere between 23 and 28 thousand.

However, in both cases, little discrimination was made between Slavophones and Greek-speaking Greeks. The "Communist" label was sufficient for their relentless persecution by a monarchic state that was in the process of integrating NATO. The rest, not being dubbed "Communists", were considered Nazi collaborators and were equally fiercely persecuted. During the decades of the Cold War their properties were confiscated on charges of treason, an attitude not unprecedented throughout Europe at that time. According to the Potsdam Conference resolutions, 2-3 million German ethnics were deported from Czechoslovakia and their properties were confiscated; many of their leaders were executed. Similarly, German ethnics were expelled from Poland and their properties were also confiscated. Danzig, was renamed to the Polish "Gdansk".

Due to the Slavophone's flight, the Greek government's reaction was mild in comparison to those of other European governments. The only concrete measure taken was the interdiction of their return and the confiscation of their properties, along with those of Greek Communists. The 1951 official Greek census revealed that 42,000 Slavophones had remained in Greece. Greek intelligence during the civil war had shown them to be of Greek conscience; reports stated that they had formed home-guard units to resist the Yugoslav or Bulgarian guerillas and the NOF. [5]

This is a particularly painful chapter in Greek modern history, but trying to give it a Slavomadeconian hue is grasping at straws.

FYROM vs Greece: who is the best US client?

After the Second World War, and until the mid 1970's Greece was, by any standard, a US protectorate. Greece became a NATO member in 1952 and four US military bases were installed there (Gournes, 1954; Hellenikon, 1956; Souda, 1959; Nea Makri,1963). Throughout the Cold War US interventions grew heavy in Greek politics. To top all else, Greece suffered a US-supported military junta between 1967-74. This ended after the Turkish military invasion of Cyprus, which the junta Colonels did not respond to, under US assurances that they were just "army drills". The carefully exploited tensions with Turkey also dictated a subservient posture of Greek politicians, in order to avoid US reprisals in the form of military aids to Greece's NATO "ally". The first steps toward emancipation of Greece from US domination began after Constantinos Karamanlis (uncle) decided to apply for accession to the EC (now EU). Serving several mandates as Greek PM throughout the Cold War, he knew first hand the US control of the political system. Thus, as an EC/EU member, Greece found itself in another sphere of influence, of most immediate proximity.

The collapse of the USSR and the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, presented the US foreign policy with other small countries as potential clients. The NATO bases at Gournes, Nea Makri and Hellenikon were evacuated by unilateral decision of the US in 1991. On the other hand, the post-9/11 faltering of the US hegemony and the reemergence of Russia as a global power, were the other two factors that allowed for additional steps of emancipation. Partly by coincidence and partly due to Greece's nepotistic political system, it was Constantinos Karamanlis (nephew) that would be Greek PM after 2004.

1) Karamanlis not supporting the Anan plan for Cyrpus

The very first problem that the Karamanlis government had to tackle immediately after its election in 2004, was the negotiations concerning Kofi Anan's plan for the reunification of Cyprus (after the 1974 invasion, a 40,000-strong Turkish occupation force still remains on the Northern part of the island). The US-British-inspired Anan plan foresaw a series of measures that safeguarded the British sovereignty of two areas of the island that host British army bases, of vital importance for US/British electronic espionage. The plan also suggested the reunification of the island as two "Constituent states" that both would accede to the EU. These would be governed by mixed Turkish-Cypriot and Greek-Cypriot presidencies and run by other mixed institutions (courts etc). However within this "State", Greek-Cypriot refugees from Northern Cyprus would be deprived of the right of repatriation to the North. This would not only be in contrast to the EU Acquis Communautaire of free movement and settlement, but in violation of human rights since citizens of other European countries would be free to settle in these areas.

Despite strong pressures from the US, Karamanlis' dubious position during and after the Burgenstock summit, allowed the Cypriot President Tassos Papadopoulos to openly express his opposition to this plan. During the subsequent referendum, 76% of Cypriot citizens voted against it, to the disappointment of the US and Britain.

2) Greece vetoing FYROM

As we previously mentioned, this move went entirely against stated directives of the US foreign policy and stalled the US plans for the region.

3) Greece doing business with Russia

As we said, the flanking of Russia from all sides (military, diplomatic, economic) is now a major consideration of the US foreign policy. What should be expected of US "allies" is to participate in, or at least not act against, this flanking. In 2007, after many years of deliberations, Greece and Russia agreed upon the construction of an oil pipeline between Burgas (Bulgaria) and Alexandroupolis (Greece) which would transport Russian oil and circumvent the Turkish straits of Bosporus and the Dardanelles. The agreement was signed on December 18, 2007. Greece also opted to collaborate in another Russian pipeline, Southstream, which will carry Russian gas to Europe through South Italy. The deal was signed on April 29, 2008 between Karamanlis and Vladimir Putin in Moscow and ratified by the Greek parliament on August 29. This pipeline is viewed as "competition" to the US-backed Nabucco pipeline.

The opposition of US for any Greek (or any other's for that matter) cooperation with Russia is illustrated in an interview given by Matthew J. Bryza, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, to Tom Ellis of the Greek daily "Kathimerini". This interview was given only days after the parliamentary ratification of the Southstream project (September 7, 2008), and was titled "This is no time for business with Russia". Bryza says: "... the general NATO, EU and USA position is that this is no time for business as usual with Russia. Even if there have been prior engagements, the decision for someone to go through to deepen prior engagements would imply that cooperation with Russia continues as usual, when all of us in the euroatlantic community send the clear message that this is no time to continue cooperation with Russia." Concerning Karamanlis' decision to go through with the Southstream project he states: "If [Greece] wishes to deepen its dependence on Gazprom, that is its own strategic decision. We just expect from all our allies to carry out their commitments within NATO. Commitments within EU are not our business, but within NATO they are" (quoted text translated from Greek).

In other words "Do business with Russia, if you so please, but since we (USA/NATO) consider that this is no time for such business, in so doing you would be in breach of your NATO commitments." This message could be mistook for a covert threat.

The close relation of the two issues (FYROM accession into NATO and encirclement of Russia) can be seen from an article of Edward P. Joseph published in the International Herald Tribune. This was published on August 11, 2008, hardly four days after the Russian military operations against the Georgian attack on South Ossetia and was titled "A ready response to Moscow". Therein he laments the "American weakness", which renders the US unable to do anything else than "issue statements". However, he proposes that "... there is an effective, if indirect, vehicle to convey a message, provided Washington activates it quickly. The solution is for NATO to invite Macedonia to join the alliance. Macedonia may lie 1,200 miles to the south of Georgia, but its neighbor is Kosovo - the fledgling state whose recent independence Russia has exploited to raise tensions over South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Both Macedonia and Georgia were disappointed at NATO's April summit meeting in Bucharest. Rather than receive formal bids toward membership, each received only rhetorical support from the alliance. For Georgia, this was due to European fear of angering Russia. In Macedonia's case, bitter opposition from Greece was the cause. In addition to objections to Macedonia's name, Athens also has warm relations with Moscow and its sometime client, Serbia. Greek observers believe that relations with Russia have also emboldened Athens to take such a hard line.

By inviting Macedonia in now, NATO would [...] announce to Moscow [...] that NATO is determined to continue on the path of enlargement,[...] it would send a message from the Balkans to the Caucasus about the integrity of small states."

Thus, in emulating FYROM to Georgia, he also emulates Greece to Russia as well as the two bilateral conflicts. Some would argue that these analogies are disproportionate, both in terms of size (Greece versus Russia) but also in terms of bilateral relations; it is undeniable that a Greek military intervention against FYROM is simply unimaginable. Simultaneously, Joseph waves the finger at Greece for keeping relations with Russia (or Serbia), whom US foreign policy considers their major foe in Europe. [Note: FYROM lies 1,200 miles to the East of Georgia, and not to the South.]

He also uses another "argument" to convince Greek PM Constantinos Karamanlis to reverse his positions. The argument is the reminder of his Karamanlis' slim parliamentary majority: "How to convince Greece that NATO's solidarity is more important than the name of its neighbor? Prime Minister Kosta Karamanlis may cling to a narrow parliamentary majority, but even his opposition can see that the global situation is changed." One may wonder about the relevance of Karamanlis' government majority on the FYROM dispute, and why it should be brought up by a US policy maker. Some might view that as another covert threat.

It should also be noted that what Joseph proposes is in effect punishment against Athens who "has warm relations with Moscow", thus killing two birds with one stone: including FYROM into NATO (NATO enlargement) and punishing a country for doing business with Russia (isolation of Russia). Joseph's speed in producing such a "Ready response" is certainly admirable, given the fact that he had only four days in his disposal, and considering that the Georgian attack came as a total surprise to US foreign policy analysts (according to their claims).

4) New US embassy in Skopje (FYROM capital)

In an article of August 16, 2008, titled "Embassy and CIA center?" the German magazine Der Spiegel, reveals the construction of the new US embassy building in Skopje, FYROM's capital. The embassy currently being built by the Halliburton subsidiary Brown & Roots, is going to be the largest US building in the Balkans, covering an area of 11 acres and comprising 10-15 underground floors. It is also expected to be much more than a simple embassy, which will also house CIA headquarters and a logistics center for US military presence in Kossovo, Bulgaria and Romania. The report concludes: "In any case Macedonia is considered a particularly loyal US ally in the region". The Czech newspaper SIP suggests that this building will also be used as an alternative to the Guantanamo prison, due to the undesired publicity it has recently received.

Please note that the dismantlement of three NATO bases in Greece in 1991, has been succeeded by the creation of a massive military base in Kosovo (camp Bondsteel) after 1999, and a new massive (for Embassy standards) installation in Skopje. Although many natives protested the building of this installation on a Muslim cemetery, it so seems that FYROM's government is sufficiently eager to please.

5) AMBO pipeline to pass through FYROM

FYROM is planned to provide passage to the AMBO (Albania-Macedonia-Bulgaria) oil pipeline, a major energy corridor controlled by the US. This project is very important for the consolidation of US monopoly on energy routes in Europe and for the simultaneous derailment of similar Russian projects. The AMBO pipeline is planned to be built by Halliburton, the company that also built Camp Bondsteel and is deemed of paramount importance for rendering European states ever more dependent on the US for their energy supply.

6) FYROM troops in Iraq

FYROM's eagerness to please is illustrated by its willingness to undertake tasks unpalatable to others. It was within that context that it decided to join G. W. Bush's Alliance of the Willing and send troops into Iraq, in 2003. Although these troops were a mere 36 (increased to 80 by the end of 2007, just prior to the Bucharest summit), their dispatch constituted a symbolic gesture of allegiance and a much needed media maneuver that gave the Iraq campaign a pretense of international consensus. This was not much unlike Greek participation in the Korea war, with over 10,000 troops over the period of 1950-55. But as we previously said, that was back then and more recently Greece failed to oblige.

And the winner is...

It is clear from the above that in a series of issues raking high in US agenda, Athens is a "liability" while Skopje is an "asset". Of course, on an overall basis, Greece is still tightly bound to US foreign policy. It is a NATO member, with a NATO military base operating on its soil; by no means a "renegade" state. However, where unequivocal obedience is required (You're either with us or against us in the fight against terror, as President Bush put it on 11/6/2001), even the slightest disagreement is unacceptable and punishable: "Over time it's going to be important for nations to know they will be held accountable for inactivity".

To date, Greece still remains out of the US Visa Waiver Program, in which 22 other European countries participated as of 2006. Although Greece, had already (in 2006) visa refusal rates less than 3%, it was not included in the VWP countries. Meanwhile, as of June 2008 (two months after the NATO summit), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced the signing of memoranda of understanding with seven additional European countries (Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Slovakia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta), while on June 17, 2008, the DHS also signed a (VWP) interim declaration with Bulgaria.

Although Greece in the past was in FYROM's current position of subservience, it is no more, or at least not to the same extent. So, for the attainment of US geopolitical goals, FYROM is far more useful. It is therefore not surprising that President Bush chose, without hesitation, to displease Greece, a longtime NATO ally, in order to secure the stability of a more recent and currently more useful client. This support will endure as long as FYROM is useful to US strategies and as long as these strategies remain the same. However, as global balance of powers and US administrations are susceptible to change, FYROM's usefulness is not expected to last forever.

So what if they are called Macedonia?

It is common among the Western and particularly the Anglo-Saxon media to treat Greek positions with rare irony and derision. To paraphrase John Pilger, it is a given fact that Britain's imperial success gives modern British leaders and journalists an inflated sense of significance and authority. Writes BBC's Mark Mardell in his Euroblog: "It is very easy to mock this position, and mock people do. American newspapers point out that there is a town in the US called "Athens" and ask if it should be renamed. The author of a letter to the Economist suggests Greece should henceforth be known as "The Former Ottoman Province of Greece". I ask why there is no friction between the Belgian area of Luxembourg and the neighbouring country of Luxembourg, and wonder aloud if Turkey should claim the right of ownership of all Christmas poultry." This line of commentary is particularly offensive to Greek sensitivies on the matter. Sensitivities shared not by a few, but by the majority of the Greek people. And it is typical of the time-honored colonial tradition of perceiving people of different cultures as backward, irrational and superstitious savages. At best, it reveals lack of knowledge of Balkan affairs and history, and unwillingness to be better informed before putting ideas on paper.

In practical terms, the first and simplest complication that will arise concerns the self-identification of people, in terms of nationality and citizenship. When people say: "I am Macedonian", do they mean a citizen of FYROM, or someone from the Greek province of Macedonia? In the way Americans may say, "I am from Athens, Georgia" to disambiguate their provenance, will something of the kind be foreseen for FYROM's citizens (e.g. "Slav-Macedonians", or "North-Macedonians")? Official reference to a "Macedonian" citizenship and nationality might entail monopoly of the term both in a political and an ethnological sense.

There is also the complication of geography. Assuming that "Macedonia" is simply a geographic term, defined to refer to a wider region spanning Greece, FYROM and Bulgaria (and to a lesser extent, Albania), then shouldn't the denomination like "Republic of Macedonia" be rightly considered expansionist? A Republic of "Macedonia" (as a whole), and not of a particular subdivision of it (e.g. of "Northern Macedonia", "Slav-Macedonia" or "Vardar Macedonia") would de facto imply claims to the rest of the region, even if officially denying it.

There is also the complication of historical patrimony. Having been self-proclaimed as the "Republic of Macedonia", having chosen King Philip's emblem of the 16-ray star (Vergina Sun) for its flag and having renamed the capital's airport to "Alexander the Great airport", FYROM sends clear messages regarding its policies on founding a national myth for itself. A myth attempting to usurp a historic patrimony that Greeks justifiably consider their own, since they constitute the only nation speaking the same language as the ancient Macedons, i.e. Greek.

Another complication concerns the commercial brands of several Greek products, named "Macedonian". Should FYROM reserve the sole use of this appelation d'origine, or Greece? What about labels that coincide (e.g. "Macedonian wine")? And let no one be deceived on the severity of the matter: if a region (Greek, British, or other) decided to call itself "Champagne" and to start selling sparkling wine under this appelation d'origine, the uproar from France would be such, that Greece's attitude up till now would be, in comparison, phlegmatic.

Finally, and most importantly, this issue may prove dangerous to Greek sovereignty. We already acknowledged that direct military danger from FYROM is an absurdity, given the size and infrastructures of the country, compared to those of Greece. However, we also acknowledged that such a danger may not necessarily stem from FYROM itself, but by other powers having vested interests in it, namely NATO and the US. And it may not necessarily come as brute military intervention but in subtler, but equally effective, forms. In any case, the paradigm of Yugoslavia and Kosovo serves as a powerful reminder that this is a real possibility.

A war of impressions is a good first step in that vein. On October 13, 2008, a few inhabitants of the Greek village Lofoi (near Florina) protested the operation of a firing range of the Greek Army near their fields, because of the damages caused by the explosions. The same evening, the media in FYROM reported that "Macedonians" were protesting the very presence of the Greek Army near their village. They also hosted members of the "Rainbow" party making similar claims. The next day the Foreign Ministry of FYROM filed a protest to the Greek government and Mr Gruevski protested the operation of the firing range and the conducting of drills by the Greek Army. In addition, four FYROM journalists [6] were apprehended by the police filming the firing range installations without authorization. The police brought them to the police station for identity control, as stipulated by Greek law and the four were released later that day. The Foreign Ministry of FYROM again protested for the implementation of Greek law, on Greek soil.

Clearly, army drills and constraints in the recording of army installations fall in the very core of issues regarding national sovereignty and security. What in essence happened during this incident is that Mr Gruevski attempted to interfere with application of Greek law and Greek sovereignty, whose legitimacy he effectively questioned.

So, it is not a case of simple ego and backward mentality. It is the issue of the possible monopoly of a name in ethnological, historical, geographical and commercial terms and the endangerment of Greek sovereignty. Such concerns have parallels in the Balkan region. When in October 1992, the Republic of Slovenia published a temporary banknote, bearing a watermark of the historical symbol of the old principality of Carinthia a stormy reaction was raised among Carinthian Austrians, who accused Slovenia of fueling nationalistic claims for Carinthia. After a heated debate in the local parliament, the federal government in Vienna was asked to intervene with Slovenian authorities, who finally gave assurances that they have no claims on the province and agreed to substitute the banknote. More recently, a stir has been provoked by the depiction of the Prince's Stone on the 2 cent Slovenian Euro coin. This is a fragment of an ancient Roman column where Carinthian Dukes used to be installed. Since this may be considered a Carinthian symbol, the Carinthian state government issued a resolution of protest on October 25, 2005.

Finally, a note on Luxemburg. The Belgian province seceded from the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg as a result of the Belgian Revolution (1830) that led to the formation of Belgium (formerly part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands). William I of the Netherlands would not recognize Belgium (and consequently the seceded region of Luxemburg) until 1839, when he was obliged to do so (Treaty of London) by the European Great Powers. So, even if there is no friction now, there was in the past. Moreover, such comparisons are not only erroneous with respect to their historical facts, some of which are conveniently omitted. They are also off the point because they disregard (i) the long "normalization period" in the relations among Central-European states, a luxury non-existent in the Balkans, and (ii) the fact that disputes like the one in Luxemburg, which occur in the immediate neighborhood of major European powers, are no longer resolved by gun power. This "preferential" treatment is reserved for faraway and obscure regions like the Balkans, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. The "humanitarian bombings" and "democratization invasions" have yet to allow true reconciliation between the peoples of these regions. So, to someone acquainted to recent Balkan history, such comparisons don't only constitute serious errors, but also cruel jokes.

In the third part, we will proceed to the presentation of some conclusions.

References

[1] "Greece's Macedonian Adventure: The Controversy over FYROM's Independence and Recognition". From a revised version of an essay appearing in the newly-published book by Macmillan Press Ltd (UK, USA 1999), edited by James Pettifer.

[2] Evangelos Kofos, "The Macedonian Question; the Politics of Mutation", Balkan Studies, Vol 27, 1986, reprinted in Evangelos Kofos, National and Communism in Macedonia; Civil Conflict, Politics of Mutation,National Identity, New York, A. Caratzas Publisher, 1993. A year-and-a-half prior to FYROM's declaration of independence, the then PASOK Minister for Macedonia-Thrace, Stelios Papathemelis, in an article in Kathimerini (March 4,1990) wrote that : For Greece, "there is no Macedonian question" in terms of a so-called "Macedonian" minority; there is, however, a "Macedonian Question" in so far as Skopje "appropriates our history and traditions and usurps the Greek name of Macedonia. The appropriation of the Macedonian name by a (Slavic) state entity implies territorial claims", reprinted in St. Papathemelis, Politiki Epikairotita kai Prooptikes [Current politics and future prospects], Thessaloniki, Barbounakis, 1990.

[3] For the full text of Mr Gruevski's letter to Mr Karamanlis and the reply of Mr Karamanlis see here. For the reply of the EC to the letter addressed to Mr Barroso see here.

[4] Lower rates for major parties are common, since voters tend to vote more loosely with respect to their political affiliations. This is produced by the feeling that the outcome of these elections does not affect voters too much. Thus, they can more freely express their discontent to larger parties by voting smaller ones.

[5] December 17, 1949 report by Commander-in-Chief A. Papagos cited by E. Kofos in "Nationalism and Communism in Macedonia" Institute for Balkan Studies, Thessaloniki 1964, p. 187 (GFM A/59179/Γ5Ba/1949).

[6] Goran Momiroski (Горан Момироски, Channel A1 Reporter), Gorazd Comovski (Горазд Чомовски, Channel A2 Reporter), Igor Jankovski (Игор Јанковски, Channel A1 Cameraman) and Mary Jordanovska (Мери Јордановска, NOVA MAKEDONJIA Reporter).

Add new comment