As a rule, political economists of the present day do not take the trouble to study the history of money; it is much easier to imagine it and deduce the principles of this imaginary knowledge Alaxander del Mar, A History of monetary systems (1901)

FYROM's Slavomacedonism, Part III: some final conclusions on the Greece-FYROM conflict

Note: This article originally appeared on Dec. 19, 2008 on ZNet. No changes have been made, apart from formatting and reassigning certain dead links.

In Part I we saw the historical background of the "Macedonian question" focusing on the period from the Crimean War to the dismemberment of Yugoslavia. In Part II we examined its more recent developments, particularly after 1991. In particular, we examined the US intervention in the matter after 1991.

Concerning the Greece-FYROM conflict, a recurring theme in the arguments of many analysts is FYROM's inherent instability. Since this is an important factor in the equation, let us see what this amounts to.

FYROM's internal and external issues

Albanian minority

An important point, as we previously mentioned concerns the Albanian minority. The grievances of this minority, and their expression by military means through the NLA, brought FYROM to the brink of all-out civil war in 2001. The implementation of the Ohrid agreement, which was imposed by the US/EU to end this conflict, brought additional problems and destabilization. A large portion of the Slavophone population of FYROM objected the concessions being made to Albanians. Through a referendum they tried to block the law implementing the Ohrid agreement, and it was only through bribery and intimidation that the referendum was boycotted and effectively defeated. This left FYROM's government greatly exposed, and it required US intervention to avoid further destabilization (see comments in Part II).

More recently, allegations of fraud during the elections of June 1, 2008, brought the two Albanian parties (Democratic Union for Integration, DUI, and the Democratic Party of Albanians, DPA) to combat positions. One person was killed and nine were injured during fire-exchange on election day, leading to a rerun of the polling in several polling stations in Albanian districts. Although these incidents did not escalate, the intra-Albanian feud scuttled FYROM's aspirations for NATO and EU integration. In a report issued on November 5, 2008, the European Commission found FYROM unsuitable for candidacy for accession due to many pending issues. Mainly, these concern the existence of a functioning democracy, rule of law and minority rights.

The Albanian minority of FYROM constitutes a destabilizing element, which is expected to increase, based on demographics. A very sensitive topic for FYROM's Slavophones concerns the high birth rates of the Albanian minority. Slavophones feel threatened of becoming a minority themselves, but even if this does not happen in the near future, balances are already shifting. It is an open question how the Albanian minority will behave in the years to come, particularly if it is encouraged by its increase in numbers. The stance of Albania at such a time, though friendly at the moment, is another unknown in the equation.

In any case, it is certain that FYROM's Albanophones have no affinity to Slavomacedonism. It is quite probable, as they grow in numbers, that they demand to stop being excluded from international organizations for an ideal they do not ascribe to.

Bulgaria

Over the last few years many Slavophones of FYROM have come to overtly proclaim a Bulgarian national conscience. Bulgaria traditionally considered the Slavophone populations of the whole region of Macedonia as Bulgarians and actively pursued their appropriation either by peaceful means or by coercion. This was in part due to the linguistic closeness of the these populations to Bulgarians and might be a valid argument. On the other side, these populations themselves had come to acquire such a conscience by the time of the Second World War. While the majority of Slavophones living in Greece migrated to Bulgaria during the interwar population exchanges, those living in the then called Vardarska Banovina remained in Yugoslavia. Notably, when German and Bulgarian troops invaded Yugoslavia, they were perceived as liberators by many of those Slavophones. However, after the defeat and departure of axis forces from Yugoslavia (along with the Bulgarians), the process of "Macedonization" of the Slavophone populations began under Tito. This process might be viewed as largely successful, however, recent developments may contradict this conclusion.

Partly due to Bulgaria's recent accession to the EU, which increased employment prospects for its citizens, and partly due to the cultural and linguistic closeness with Bulgarians, 60 thousand FYROM citizens have applied for Bulgarian passports. Under recent Bulgarian legislation this became possible if the applicants signed an official declaration of being Bulgarians in origin. Some 14 thousand citizens of FYROM were thus granted Bulgarian passports between 2001-07. Most strikingly, among them, was the former PM of FYROM, Ljubčo Georgievski, as well as other FYROM officials. Of course, employment and travel considerations are among prime reasons why non-EU citizens would apply for EU citizenship, Bulgarian in particular. However, it should be noted that among nationals who obtained Bulgarian citizenship between 2001-07, those of FYROM were first on the list (14,091) of a total of 31,958, amounting to 44% of all new citizenships. Successful applications from FYROM, numbering only 2 million inhabitants, greatly outnumbered those from countries with much higher populations like Moldova (4,2 million), Ukraine (46.5 million) or even Russia (141 million). This not only indicates the continued interest of Bulgaria in what they have historically considered as Bulgarian land, but also exposes the superficiality of Macedonism. Indeed, such applications have mainly come from countries with Bulgarophone minorities (e.g. Moldova has a Bulgarophone minority in Bessarabia).

Serbia

FYROM-Serbia relations have been marked by the question of the autocephaly of the "Macedonian Orthodox Church" (MOC). The MOC first gained autonomous status in 1959 under pressure from the Socialist Party of Yugoslavia, and it was self-proclaimed autocephalous in 1967. However, after the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991, the question of Serb-Orthodox population and churches in FYROM brought high tension between the MOC and the Serbian Orthodox Church. The autocephaly of the former has been strongly questioned by the latter, with this issue poisoning their relations. To date the autocephaly of the MOC has not been recognized neither by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, nor by any other autocephalous church.

However, probably more important to the Serbia-FYROM relations was FYROM's decision to officially recognize the independence of Kosovo on October 9, 2008. This recognition falls within the US strategy of further "Balkanization" of the region, i.e. its subdivision to weak, quarrelling and subservient puppet states. This decision was also actively pursued by the two Albanian minority parties, DUI and DPA, as a form of allegiance to the predominantly Albanian population of Kosovo. This gesture was particularly offensive to Serbia, who saw one of its neighbors actively condoning its territorial breakup. One day later, Serbia declared the Macedonian ambassador to Belgrade persona non grata (unwanted person), and Serbia's ambassador to Skopje submitted a protest note to the Macedonian foreign ministry.

Economy

With an official 35% unemployment rate (2007 est.), a grey market amounting to 20% of the GDP, and with 30% of the population below the poverty line, FYROM is one of the poorest countries in the Balkans.[1] Complementing this grim picture is the high criminal record in FYROM, as reported by the US State Department: "Macedonia is a source, transit, and destination country for women and children trafficked for the purpose of commercial sexual exploitation. Macedonian women and children are trafficked internally, mostly from eastern rural areas to urban bars in western Macedonia."[2] Such activities have permeated the political scene of the country. MSNBC reported that Ali Ahmeti, leader of the Albanian DUI party and former leader of the NLA paramilitary "conceded in an interview with MSNBC.com that some of the rebels' funding might come from narcotics trafficking and a flourishing sex slave trade in the region. But Ahmeti, whom the Macedonian government has arrested on drug charges in the past, maintained that the volume of donations to the rebel movement made it impossible to check their source. "We try to vet all the money," Ahmeti said in an interview high in his mountain headquarters in Sipkovica in northwestern Macedonia. But even Ahmeti admitted he counts rich Balkans smugglers among his supporters. "We're not so fanatic to say that such money could not reach us," Ahmeti told MSNBC.com."

Most of FYROM's trade is conducted with its neighbors. In 2007, FYROM exported most of its production to Serbia & Montenegro (19.2%) with Greece being its third customer (10.4%). At the same time, Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia & Montenergo were FYROM's largest importers (12.9, 9.6 and 7.7% respectively) after Germany, which was the largest.[1]

Support by the US a guarantee?

Thus, FYROM has systematically decided to assume a hostile posture toward its only neighbors raising absolutely no claims against it (Serbia and Greece), neither directly, nor through a minority manipulated for this purpose. These neighbors are also among its closest commercial partners. In that respect, Mr Gruevski seems to be playing the role of a "Saakashvili of the Balkans", i.e. leading his country into unwarranted conflicts with its neighbors, simply to act as the spearhead of US foreign policy. This similarity is even more accentuated by both leaders' utter surprise when their protector failed to come to their aid when most needed. The cavalry never showed up, neither after Greece's veto at the Bucharest NATO summit, leaving FYROM out in the cold, nor during the South Ossetia war, leaving Georgia exposed to Russia's retaliation. As a result, FYROM is now found gridlocked among four neighbors who would either like to see it split (formation of Great Albania, and/or some sort of annexation to Bulgaria), or who have been so threatened by it, that they would not move an inch to help it in duress. The only factor that seems to be keeping the state cohesion is US intervention for as long as it holds. However, we should bear in mind the Kurdish uprising during the first Gulf War, which was instigated by US promises of a Kurdish state. In that instance, when the Allied forces left, the US allowed Saddam Hussein to remain in power. This choice left the Kurdish population of Iraq greatly unprotected. Yet, the US did nothing to help a people which their promises had left so exposed.

We should also bear in mind that the position of the US foreign policy has changed on this issue (like in many others), depending on the balance of powers at a given moment: Tito renamed "Vardarska" to "Macedonia" before his split with Stalin transformed him from a Communist menace to a US favorite. Then, the US State Department responded promptly through Roosevelt's Secretary of State, Edward R. Stetinius, Jr:[3]

This government considers that any mention to "Macedonian Nation", "Macedonian Fatherland" or "Macedonian Identity" is unjustified and demagogic; it does not represent national of political reality, perceiving it, in its present resurgence, as a probable cover for offensive actions against Greece. The official policy of this government is to take the necessary steps against those who will aid Yugoslavia or Bulgaria to raise the "Macedonian Question" at the expense of Greece.

Some decades later, this line was reversed. After the Greek veto during the Bucharest NATO summit, Assistant Secretary of State Daniel Fried declared:

...Macedonian language exists. Macedonian people exist. We teach Macedonian at the Foreign Service Institute... There is also the historic Macedonian province, which is different from the country. And it's important. It's quite clear that the government in Skopje, what we Americans call the Government of Macedonia, has no claims [against Greece]. We recognize the difference between the historic territory of Macedonia, which is, of course, much larger than the current country.

This ease of the US in changing positions, should greatly alarm their current "allies", as their alliance may cease at any moment.

To recapitulate, the combined factors of: (i) domestic Albanian insurgency, (ii) Bulgarian concealed expansionism, (iii) open fronts with Greece and Serbia and (iv) the country's depressingly faltering economy, are expected to put FYROM under strong centrifugal forces in the future. Without a strong external cohesive factor, such as currently provided by the US, this artificial state is condemned to collapse. Let us not forget that in 2001, FYROM avoided civil war only due to US/EU intervention.

There is one side that argues that precisely because of that instability, Greece should back down from all its objections, since the rapid integration of FYROM into the Euroatlantic structures would be the only guarantee for its stability and peace in the region. There is also another side that claims that due to that instability, Greece should not compromise: it is FYROM that has all the more reasons to compromise. And even if it doesn't, that shouldn't alarm Greece: FYROM's days are numbered and the problem for Greece will be solved by FYROM's own collapse. Both views are single-sided and deficient. The former entirely disregards frictions that cannot possibly be overlooked, particularly in a history-loaded region like the Balkans; the latter disregards the dynamics that will develop after the collapse of yet another Balkan state. However, they both have their valid points: it is in FYROM's best interest to back down from a maximalist position that threatens and vexes Greece, in order to assure its easy integration in international organizations; it is in Greece's (and the region's) best interest to yield certain concessions that will allow FYROM a compromise that will foster its stability. Thus, a face-saving compromise is sought.

A possible way out of the Greece-FYROM conflict

Over the last years, a large part of Greek public opinion has made the painful concession for a denomination including the term "Macedonia". A poll after the Bucharest veto indicated that 36.5% of Greeks would accept a composite denomination including the term "Macedonia", with a 61.7% opposing it. An October 2008 poll indicated that 43% of Greeks considered that "Northern Macedonia" could "probably" (32%) or "definitely" (11%) be an acceptable solution, with 53% rejecting it. Such an arrangement is not considered "just" by most Greeks (probably not even by myself), but is reluctantly accepted by many, considering that absolute justice has never existed and is not to be hoped for.

It is clear that a resolution of the Greece-FYROM conflict would be in the interest of both countries. Continuation of the current situation entails, as we previously mentioned, the possibility of FYROM's collapse, with serious repercussions for its citizens and for regional stability, as well. Both arguments previously cited seem to carry weight. However, the shared danger of regional destabilization by FYROM's eventual collapse, cannot outweigh FYROM's danger to Greece as a vehicle of irredentism and usurpation of historical patrimony and national heritage. Indeed, FYROM seems to be a destabilizing factor in the region. The only incentive for Greeks to condone such a conciliatory solution, would be the definitive settlement of all other issues raised by FYROM. Thus, FYROM would have to make clear in every possible way that it does not constitute a threat to Greece, even indirectly. In the absence of such guarantees, even the portion of Greeks that would accept a composite denomination with the term "Macedonia", do not seem ready to proceed to any agreement. Polls after the Greek veto (i.e., when such guarantees were inexistent) showed 92-95% approval rates for the Greek government's decision to veto. So what might a viable solution look like?

Name: For a solution to work out, FYROM should accept a composite name for all purposes, with the use of a proper descriptor. This descriptor should also apply to all other pertinent concepts, e.g. those of nationality, citizenship, language etc. This name should show that FYROM constitutes a part and not the whole of the region of Macedonia. As Greek journalist Stavros Lygeros argued, if Greece decided to invoke the right of self-determination and rename itself to "Republic of Europe", its citizens "Europeans", its language and nationality "European", then wouldn't that constitute usurpation of a term denoting the whole of the European continent and culture? Wouldn't the rest of the European states protest? If FYROM has rights to the term "Republic of Macedonia", doesn't Greece have even more rights to the term "Republic of Europe", considering that Europe is the name of a young girl from the Greek mythology? This latter, hypothetical, demand is as lacking in seriousness as the former. However, many Western analysts have grown accustomed to considering FYROM's demand as quite serious.

A small detail that evades most foreign analysts is that "the name" is not merely the name under which FYROM would be admitted to the UN, NATO, or other international organizations. Not even the name to be used in bilateral relations. It is the constitutional name of FYROM, the only truly relevant and legally binding denomination, the one appearing in passports and used for trade. In that sense, it would take a constitutional change for this solution to be truly definitive and sustainable.

That being said, what might be an acceptable name? The proposed name "New Macedonia" ("Nova Makedonia" in Slav) alludes to historic or ethnic continuity with something "old", e.g. "New Zealand" (given by Dutch cartograhers after the Dutch province of Zeeland), "New Amsterdam" given by the Dutch settlers and then changed to "New York" after the British conquered it, all were named to reflect the historic and ethnic origins of their settlers. This would be inappropriate in this case, as the Slavophones of FYROM are not the descendents of ancient Macedonians. Also, "Northern Macedonia" has been proposed, which however alludes to countries having been artificially partitioned by war and occupation, like "Northern Cyprus", "North Korea", or "North Vietnam". It usually implies a "Southern" part that awaits reunification with the Northern brother. This might further fuel FYROM's irredentism and the ideoogy of the "partitioned Macedonia".[4]

Another possibility might be "Upper Macedonia" ("Gorna Makedonia" in Slav), which is a name with a neutral, geographical descriptor that does not present us with any of the previous problems. "Vardar Macedonia" (or "Vardarmakedonia") is also a geographically described name (after the Vardar river) which has the additional advantage of alredy being used by FYROM to geographically describe its territory.[4]

"Slav Macedonia" or "Slavomacedonia" would be a name that properly describes the ethnic descent (Slavic) and geographical location (region of Macedonia) of the country's Slavophone population, without vexing the Greeks. It would also be suitable for the description of their language and nationality (Slav-Macedonian, or Slavomacedonian).[4] It is quite probable though, that FYROM's Albanians would not accept this since, as we said, they are not Slavs. In that case "Slavoalbanian Macedonia" could be a good compromise, which would (for the first time) make reference to the second largest ethnic group of the country. Then, nationality and language could also described by terms suited to, and accepted by each particular ethnic group, i.e. "Slavomacedonian" and "Albanomacedonian".

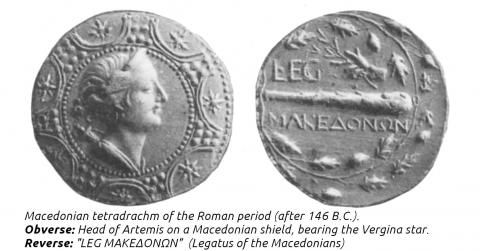

Symbols: FYROM should also reverse its inflammatory policy of using ancient Greek symbols (e.g. the Vergina sun on its flag) and personalities, like Alexander the Great (new name of Skopje Airport and statues erected throughout the country).

Irredentism: It should also revise its constitution in a manner that it would beyond doubt remove threats to Greek sovereignty and territorial integrity (see comments here). Finally, it should drop issues relating to minorities, which as previously argued, are unfounded after the interwar population exchanges and even more so after the post-war flight from Greek Macedonia of Slavophone communists and Nazi collaborators.

It is understandable that such concessions from FYROM's side will negate the whole construct built after the Second World War and will be equally painful to its inhabitants as well; probably as painful as would be for Greeks to share the term "Macedonian" with another nation. However, these painful concessions from both sides are necessary for long-term peaceful relationships. It seems that this has been understood by FYROM's population. A March 2008 poll (i.e. before the Bucharest summit), showed that 82% opposed change of FYROM's constitutional name for NATO accession. However, after the Greek veto, polls showed that this dropped to 53%, with 36% accepting a name change. What remains to see, is whether political elites having risen to prominence based on maximalist views and strategies will choose to jeopardize their short-term power for long-term stability. It also remains to see whether the elites of both countries will come to a solution without the mediation of their common patron, the US.

A personal perspective

I should make clear that I am neither a professional historian, nor do I aspire to be one. Not being one has its disadvantages, as the breadth and depth of my historical training are certainly not those of a professional. On the other side, to the measure that I keep my facts straight and double-check my references, this has also its advantages, as it keeps me free from specific schools of thought. Ideological blindness is a serious illness, to which trained professionals (particularly in the Political, Social, Economic and Historical disciplines) are very susceptible.

I should also make clear that, concerning the Greece-FYROM conflict, I am not an impartial observer, nor could I be one, since I am Greek. I tend to be biased and more tuned to Greek sensitivities, however I hope it's clear that I bear no animosity toward "the other side", nor do I desire its annihilation (Note: the views of certain Greek professional historians have shown me that strong biases do not only stem from national sentiment, but also from following the dictated ideology that serves certain geopolitical interests. Being a professional usually entails the additional disadvantage of having a boss with specific interests, whether you work for a newspaper, a University, or an NGO; however, this is another story).

These being said, my personal view on the matter is that disputes can be resolved in roughly two ways: internally (peacefully or not), or with the "aid" of an external arbiter (again, peacefully or not). In that latter case, whoever assumes the role of the arbiter does so, not out of altruism, but with his own interests in mind. These often tend to diverge from those of the conflicting sides. And usually, by accepting this arbitration, the conflicting sides cede power and sovereignty that was their own to begin with. The Balkans have traditionally been the site where foreign powers exercised power for their own interests and the Balkan states were only too happy to succumb to this divide-and-conquer policy and pay a heavy price in blood (this will be analyzed in more depth elsewhere).

Today, the main arbiters for the Balkans are US/NATO and the EU, with Russia regaining much of its influence and Turkey becoming a very strong player. Some Balkan countries are pro-US, others are pro-EU, while others are pro-Russian.

Who will become pro-Balkan?

References

[1] Source: CIA Factbook, www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mk.html

[2] US State Department: "Trafficking in Persons Report 2008"

[3] Circular No 868014/26-12-44.

[4] Stavros Lygeros, "En onomati tis Makedonias" ("In the name of Macedonia"), Livani eds., 2008.

Add new comment