You may have all the money, Raymond, but I have all the men with guns.Vice President Francis Underwood, House of cards, (2013)

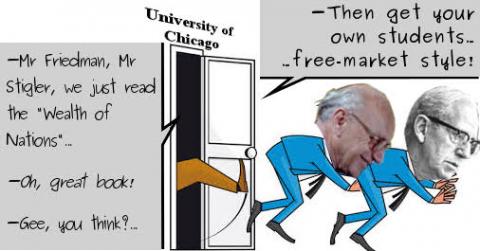

Adam Smith the educator

This article is part of the series "The Adam Smith muppet show".

What are Adam Smith's views on university education, remuneration of teachers, tenured university Professors, and public education? His academic desciples might condsider them extreme, to say the least.

Rule 1: Salaried university professors are useless

Corollary: Self-respecting University Professors teaching free-market economics should all voluntarily resign

Smith is particularly opposed to Professors being hired and payed by the Universities, as this will allow them to become neglectful, which he sees as the natural evolution of every professional with a secure salary. He prefers for the students to vote with their wallets, thus keeping the Professors on their toes:

The endowments of schools and colleges have necessarily diminished, more or less, the necessity of application in the teachers. Their subsistence, so far as it arises from their salaries, is evidently derived from a fund, altogether independent of their success and reputation in their particular professions.

In some universities, the salary makes but a part, and frequently but a small part, of the emoluments of the teacher, of which the greater part arises from the honoraries or fees of his pupils.

In other universities, the teacher is prohibited from receiving any honorary or fee from his pupils, and his salary constitutes the whole of the revenue which he derives from his office. His interest is, in this case, set as directly in opposition to his duty as it is possible to set it. It is the interest of every man to live as much at his ease as he can; and if his emoluments are to be precisely the same, whether he does or does not perform some very laborious duty, it is certainly his interest, at least as interest is vulgarly understood, either to neglect it altogether, or, if he is subject to some authority which will not suffer him to do this, to perform it in as careless and slovenly a manner as that authority will permit. If he is naturally active and a lover of labour, it is his interest to employ that activity in any way from which he can derive some advantage, rather than in the performance of his duty, from which he can derive none.

If the authority to which he is subject resides in the body corporate, the college, or university, of which he himself is a member, and in which the greater part of the other members are, like himself, persons who either are, or ought to be teachers, they are likely to make a common cause, to be all very indulgent to one another, and every man to consent that his neighbour may neglect his duty, provided he himself is allowed to neglect his own. In the university of Oxford, the greater part of the public professors have, for these many years, given up altogether even the pretence of teaching.

If the authority to which he is subject resides, not so much in the body corporate, of which he is a member, as in some other extraneous persons, in the bishop of the diocese, for example, in the governor of the province, or, perhaps, in some minister of state [...] All that such superiors, however, can force him to do, is to attend upon his pupils a certain number of hours, that is, to give a certain number of lectures in the week, or in the year. What those lectures shall be, must still depend upon the diligence of the teacher;

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations (BOOK V, CHAPTER I, p. 820-821)

Adam Smith pulls no punches when he speaks his mind about his former colleagues:

The person subject to such jurisdiction is necessarily degraded by it, and, instead of being one of the most respectable, is rendered one of the meanest and most contemptible persons in the society.

If in each college, the tutor or teacher, who was to instruct each student in all arts and sciences, should not be voluntarily chosen by the student, but appointed by the head of the college; and if, in case of neglect, inability, or bad usage, the student should not be allowed to change him for another, without leave first asked and obtained; such a regulation would not only tend very much to extinguish all emulation among the different tutors of the same college, but to diminish very much, in all of them, the necessity of diligence and of attention to their respective pupils.

Those parts of education, it is to be observed, for the teaching of which there are no public institutions, are generally the best taught.

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations (BOOK V, CHAPTER I, p. 822-824)

Secure teaching posts are counterproductive, and public universities promote useless sciences:

In modern times, the diligence of public teachers is more or less corrupted by the circumstances which render them more or less independent of their success and reputation in their particular professions. Their salaries, too, put the private teacher, who would pretend to come into competition with them, in the same state with a merchant who attempts to trade without a bounty, in competition with those who trade with a considerable one... The privileges of graduation, besides, are in many countries necessary, or at least extremely convenient, to most men of learned professions, that is, to the far greater part of those who have occasion for a learned education. But those privileges can be obtained only by attending the lectures of the public teachers [...]

Were there no public institutions for education, no system, no science, would be taught, for which there was not some demand, or which the circumstances of the times did not render it either necessary or convenient, or at least fashionable to learn. A private teacher could never find his account in teaching either an exploded and antiquated system of a science acknowledged to be useful, or a science universally believed to be a mere useless and pedantic heap of sophistry and nonsense. Such systems, such sciences, can subsist nowhere but in those incorporated societies for education, whose prosperity and revenue are in a great measure independent of their industry. Were there no public institutions for education, a gentleman, after going through, with application and abilities, the most complete course of education which the circumstances of the times were supposed to afford, could not come into the world completely ignorant of everything which is the common subject of conversation among gentlemen and men of the world.

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations (BOOK V, CHAPTER I, p. 838-839)

Adam Smith seems to have been consistent with his teachings. While he did receive a salary from the University of Glasgow, as attested by this pay slip from the University's archives:

!["Received by me Adam Smith Professor in the College from Mr Matthew Morthland Factor to the College of Glasgow; the sum of fiftie merk [...] money being in full payment of my salary payable rent of the annual rents from the term of Martinmass [Nov. 11] 1756 to the term of Martinmass [...] 1757 this thirteenth day of december one thousand seven hundred and fiftyseven years witness my hand. Adam Smith"Photo on hold pending permission for repupblication by the University of Glasgow](http://www.gla.ac.uk/media/media_114400_en.jpg)

One of Adam Smith's receipts for his salary, 13th December 1757 mentioning:

"Received by me Adam Smith Professor in the College from Mr Matthew Morthland Factor to the College of Glasgow; the sum of fiftie merk [?] money being in full payment of my salary payable rent of the annual rents from the term of Martinmass [Nov. 11] 1756 to the term of Martinmass last 1757 whereof we [?] earned and hereby discharged at Glasgow this thirteenth day of december one thousand seven hundred and fiftyseven years witness my hand. Adam Smith"

(University of Glasgow Archives & Special Collections, University collection, GB 248 GUA 58174; republished with permission).

... he did take fees from his students, which he returned when he resigned his post at the end of 1763, in the middle of his teaching duties. Actually, as his students refused to be reimbursed, he had to shove the money into their pockets:

"You must not refuse me this satisfaction. Nay, by heavens, gentlemen, you shall not;" and seizing by the coat the young man who stood next to him, he thrust the money into his pocket, and then pushed him from him. The rest saw it was in vain to contest the matter, and were obliged to let him take his own way.

Lord Alexander Fraser Tytler Woodhouselee, Memoirs of the life and writings of the Honourable Henry Home of Kames, Edinburgh (1814), vol. 1, p. 278.)

Rule 2: Women are better off without public education

I don't know whether anyone has ever examined Adam Smith through the lenses of feminism, but he was quite happy that women are not corupted by undertaking useless studies:

There are no public institutions for the education of women, and there is accordingly nothing useless, absurd, or fantastical, in the common course of their education. They are taught what their parents or guardians judge it necessary or useful for them to learn, and they are taught nothing else. Every part of their education tends evidently to some useful purpose; either to improve the natural attractions of their person, or to form their mind to reserve, to modesty, to chastity, and to economy; to render them both likely to became the mistresses of a family, and to behave properly when they have become such. In every part of her life, a woman feels some conveniency or advantage from every part of her education. It seldom happens that a man, in any part of his life, derives any conveniency or advantage from some of the most laborious and troublesome parts of his education.

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations (BOOK V, CHAPTER I, p. 838-839)

The clincher:

And then he proceeds to ask:

Ought the public, therefore, to give no attention, it may be asked, to the education of the people?

Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations (BOOK V, CHAPTER I, p. 838-839)

The reply is entirely counterintuitive and totally incosistent with the above-mentioned disquisition (welcome to Smithian studies...). And will be fittingly presented in "Adam Smith, the Statist".

Add new comment